| Edit | Map | Home | New Post | New Gallery |

Support

|

| |

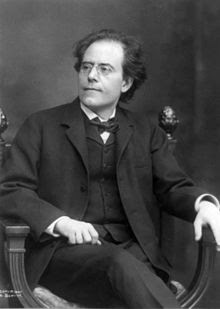

Gustav Mahler ( German: Gustav Mahler ; July 7, 1860 [1] [2] […] , Kalishte , Kingdom of Bohemia , Austrian Empire [3] [4] - May 18, 1911 [1] [2] […] , Vienna , Austria-Hungary [5] [4] [...] ) is an Austrian composer, opera and symphony conductor . During his lifetime, Gustav Mahler was famous primarily as one of the greatest conductors of his time, a representative of the so-called "post-Wagner five". Although Mahler never studied the art of conducting an orchestra himself and never taught others, the influence he had on his younger colleagues allows musicologists to speak of the Mahlerian school, including such outstanding conductors as Willem Mengelberg, Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer . During his lifetime, the composer Mahler had only a relatively narrow circle of devoted admirers, and only half a century after his death did he receive real recognition as one of the greatest symphonists of the 20th century. Mahler's work, which became a kind of bridge between the late Austro-German romanticism of the 19th century and the modernism of the early 20th century, influenced many composers, including such diverse ones as representatives of the New Vienna School , on the one hand, Dmitri Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten - with another. The legacy of Mahler as a composer, relatively small and composed almost entirely of songs and symphonies , has become firmly established in the concert repertoire over the past half century, and for several decades now he has been one of the most performed composers. Together with Hans Richter , Felix Motl , Arthur Nikisch and Felix Weingartner, Mahler formed the so-called "post-Wagnerian Five", which ensured - along with a number of other first-class conductors - the dominance of the German-Austrian school of conducting and interpretation in Europe [235] . This dominance in the future, along with Wilhelm Furtwängler and Erich Kleiber , was consolidated by the so-called "conductors of the Mahler school" - Bruno Walter , Otto Klemperer , Oskar Fried and the Dutchman Willem Mengelberg [235] [236]. Mahler never gave conducting lessons and, according to Bruno Walter, he was not a teacher by vocation at all: “... For this he was too immersed in himself, in his work, in his intense inner life, he noticed too little those around him and his surroundings” [ 237 ] . Students called themselves those who wanted to learn from him; however, the impact of Mahler's personality was often more important than any lessons learned. “Consciously,” recalled Bruno Walter, “he almost never gave me instructions, but an immeasurably large role in my upbringing and training was played by the experiences given to me by this nature, unintentionally, from the inner excess poured out in the word and in music. […] He created an atmosphere of high tension around him…” [238] . Mahler, who never studied as a conductor, was apparently born; in his management of the orchestra there were many things that could not be taught or learned, including, as the eldest of his students, Oscar Fried, wrote, “a huge, almost demonic power radiated from his every movement, from every line of his face” [ 239] . Bruno Walter added to this "a spiritual warmth that gave his performance the immediacy of personal recognition: that immediacy that made you forget ... about careful learning" [240] . It was not given to everyone; but there was much more to learn from Mahler as a conductor: both Bruno Walter and Oskar Fried noted his exceptionally high demands on himself and on everyone who worked with him, his scrupulous preliminary work on the score, and in the process of rehearsals - just as thorough working out of the smallest details; neither the musicians of the orchestra, nor the singers, he forgave even the slightest negligence [241] [242] . The statement that Mahler never studied conducting requires a reservation: in his younger years, fate sometimes brought him together with major conductors. Angelo Neumann recalled how in Prague, attending a rehearsal of Anton Seidl , Mahler exclaimed: “Oh my God! I didn’t think it was possible to rehearse like that!” [243] According to contemporaries, Mahler as a conductor was especially successful in compositions of a heroic and tragic nature, consonant with Mahler as a composer: he was considered an outstanding interpreter of symphonies and operas by Beethoven, operas by Wagner and Gluck [244 ] . At the same time, he had a rare sense of style, which allowed him to achieve success in compositions of a different kind, including Mozart's operas, which he, according to I. Sollertinsky, rediscovered, freeing from "salon rococo and cutesy grace", and Tchaikovsky [241] [245] . Working in opera theaters, combining the functions of a conductor - an interpreter of a musical work with directing - subordinating to his interpretation of all components of the performance, Mahler made a fundamentally new approach to the opera performance available to his contemporaries [ 114] . As one of his Hamburg reviewers wrote, Mahler interpreted music in terms of the stage performance of opera and theatrical production in terms of music . “Never again,” Stefan Zweig wrote about Mahler’s work in Vienna, “I have not seen such integrity on stage as it was in these performances: in terms of the purity of the impression they make, they can only be compared with nature itself ... ... We young people learned from him love perfection" [246] . Mahler died before the possibility of a more or less listenable recording of orchestral music was possible . In November 1905, he recorded four fragments from his compositions at the Welte Mignon firm , but as a pianist [248] [K 3] . And if a non-specialist is forced to judge about Mahler the interpreter solely by the memoirs of his contemporaries, then a specialist can get a certain idea about him by his conductor's retouches in the scores of both his own and other people's compositions [247] . Mahler, written by Leo Ginzburg, one of the first to raise the issue of retouching in a new way: unlike most of his contemporaries, he saw his task not in correcting "author's mistakes", but in ensuring the possibility of correct, from the point of view of the author's intentions, perception of the work, giving preference to the spirit before the letter [249] . Retouches in the same scores changed from time to time, as they were usually done at rehearsals, in the process of preparing for a concert, and took into account the quantitative and qualitative composition of a particular orchestra, the level of its soloists, the acoustics of the hall, and other nuances [250 ] . Mahler's retouches, especially in the scores of L. van Beethoven , who occupied a central place in his concert programs, were often used by other conductors, and not only by his own students: Leo Ginzburg names, in particular, Erich Kleiber and Hermann Abendroth [251] . In general, Stefan Zweig believed, Mahler the conductor had much more students than is commonly thought: “In some German city,” he wrote in 1915, “the conductor raises his baton. In his gestures, in his manner, I feel Mahler, I do not need to ask questions to find out: this is also his student, and here, beyond the limits of his earthly existence, the magnetism of his life rhythm is still fertilizing . Mahler composer [ edit | edit code ]Musicologists note that the work of Mahler the composer, on the one hand, certainly absorbed the achievements of the Austro-German symphonic music of the 19th century, from L. van Beethoven to A. Bruckner : the structure of his symphonies, as well as the inclusion of vocal parts in them, is the development innovations of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony , his "song" symphonism - from F. Schubert and A. Bruckner, long before Mahler, F. Liszt (following G. Berlioz ) abandoned the classical four-part structure of the symphony and used the program ; finally, from Wagner and Bruckner, Mahler inherited the so-called "infinite melody" [253] [254]. Mahler, of course, was also close to some features of P. I. Tchaikovsky's symphonism , and the need to speak the language of his homeland brought him closer to the Czech classics - B. Smetana and A. Dvorak [255] . On the other hand, it is obvious to researchers that literary influences were more pronounced in his work than musical ones proper; this was noted already by Mahler's first biographer, Richard Specht [de] [256] . Although even the early Romantics drew inspiration from literature and through the lips of Liszt proclaimed "the renewal of music through a connection with poetry", very few composers, writes J. M. Fischer, were such passionate book readers as Mahler [ 257] . The composer himself said that many books caused a change in his worldview and sense of life, or, in any case, accelerated their development [258]; he wrote from Hamburg to a Viennese friend: “... They are my only friends who are with me everywhere. And what friends! […] They are getting closer and closer to me and bring me more and more comfort, my true brothers and fathers and beloved” [259] . Mahler's circle of reading extended from Euripides to G. Hauptmann and F. Wedekind , although in general the literature of the turn of the century aroused only a very limited interest in him [260] . His work was most directly affected at different times by hobbies Jean Paul , whose novels organically combined idyll and satire, sentimentality and irony, and Heidelberg romantics : from the collection " Magic Horn of the Boy " by A. von Arnim and C. Brentano , he for many years scooped texts for songs and separate parts of symphonies [261] [262] . Among his favorite books were essaysF. Nietzsche and A. Schopenhauer , which is also reflected in his work [263] [264] ; one of the writers closest to him was F. M. Dostoevsky , and in 1909 Mahler said to Arnold Schoenberg about his students: “Make these people read Dostoevsky! This is more important than counterpoint . ” [265] [266] . Both Dostoevsky and Mahler, writes Inna Barsova , are characterized by "the convergence of the mutually exclusive in genre aesthetics", the combination of the incompatible, creating the impression of inorganic form, and at the same time - the constant, painful search for harmony that can resolve tragic conflicts [267]. The mature period of the composer's work passed mainly under the sign of J. W. Goethe [268] . Mahler's symphonic epic [ edit | edit code ]... What music speaks about is only a person in all his manifestations (that is, feeling, thinking, breathing, suffering) — Gustav Mahler [269]

Scholars consider Mahler's symphonic heritage as a single instrumental epic (I. Sollertinsky called it a "grand philosophical poem" [270] ), in which each part follows from the previous one - as a continuation or negation; his vocal cycles are most directly connected with it, and the periodization of the composer's work, accepted in literature, also relies on it [271] [272] . The countdown of the first period begins with "The Song of Lamentation", written in 1880, but revised in 1888; it includes two song cycles - " Songs of the Wandering Apprentice " and " Magic Horn of the Boy " - and four symphonies, the last of which was written in 1901 [273] . Although, according to N. Bauer-Lechner , Mahler himself called the first four symphonies "tetralogy", many researchers separate the First from the next three - both because it is purely instrumental, while in the rest Mahler uses vocals, and because it relies on the musical material and the circle of images of the "Songs of the Wandering Apprentice", and the Second , Third and Fourth - on the "Magic Horn of the Boy"; in particular, Sollertinsky considered the First Symphony as a prologue to the whole "philosophical poem" [272] [274] . The writings of this period, writes I. A. Barsova, are characterized by "a combination of emotional spontaneity and tragic irony, genre sketches and symbolism" [273] . These symphonies revealed such features of Mahler's style as reliance on the genres of folk and urban music - the same genres that accompanied him in childhood: song, dance, most often a rude landler, military or funeral march [ 273 ] . The stylistic origins of his music, wrote Hermann Danuser [de] , are like a wide-open fan [275] . The second period, short but intense, covers works written in 1901-1905: the vocal-symphonic cycles “Songs about Dead Children” and “Songs on Rückert’s Poems” and thematically related to them, but already purely instrumental Fifth , Sixth and Seventh symphonies [273] . All Mahler's symphonies were programmatic in nature, he believed that, starting at least with Beethoven, "there is no such new music that would not have an internal program" [276]; but if in the first tetralogy he tried to explain his idea with the help of programmatic titles - the symphony as a whole or its individual parts - then starting from the Fifth Symphony he abandoned these attempts: his programmatic titles gave rise only to misunderstandings, and, in the end, as he wrote Mahler to one of his correspondents, “such music is worth nothing, about which the listener must first be told what feelings are contained in it, and, accordingly, what he himself must feel” [276 ] . The rejection of the permissive word could not but entail the search for a new style: the semantic load on the musical fabric increased, and the new style, as the composer himself wrote, required a new technique; I. A. Barsova notes “a flash of polyphonicthe activity of the texture that carries the thought, the emancipation of individual voices of the fabric, as if striving for the most expressive self-expression” [277] . The universal collisions of the tetralogy of the early period, based on texts of a philosophical and symbolic nature, in this trilogy gave way to another theme - the tragic dependence of man on fate; and if the conflict of the tragic Sixth Symphony did not find a solution, then in the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies Mahler tried to find it in the harmony of classical art [273] . Among Mahler's symphonies, the Eighth Symphony stands apart as a kind of culmination, his most ambitious work [274] . Here the composer again turns to the word, using the texts of the medieval Catholic hymn " Veni Creator Spiritus " and the final scene of the 2nd part of " Faust " by J. W. Goethe [273] . The unusual form of this work, its monumentality gave researchers reason to call it an oratorio or cantata , or at least to define the genre of the Eighth as a synthesis of symphony and oratorio , symphony and "musical drama" [278] . And the epic is completed by three farewell symphonies written in 1909-1910: " Song of the Earth " ("symphony in songs", as Mahler called it), the Ninth and the unfinished Tenth. These compositions are distinguished by a deeply personal tone and expressive lyrics [279] . In Mahler's symphonic epic, researchers note, first of all, the variety of solutions: in most cases, he abandoned the classical four-part form in favor of five- or six-part cycles; and the longest, the Eighth Symphony, consists of two parts [273] . Synthetic constructions coexist with purely instrumental symphonies, while in some the word is used as an expressive means only at the climax (in the Second, Third and Fourth symphonies), others are predominantly or entirely based on a poetic text - the Eighth and the Song of the Earth. Even in four-movement cycles, the traditional sequence of parts and their tempo ratios usually change, the semantic center shifts: with Mahler, this is most often the finale [279]. In his symphonies, the form of individual parts, including the first, also underwent a significant transformation: in later compositions, the sonata form gives way to a through development, song variant-strophic organization. Often, in Mahler, various principles of shaping interact in one part: sonata allegro , rondo , variations , couplet or three-part song; Mahler often uses polyphony - imitation, contrast and polyphony of variants [279] . Another technique often used by Mahler is a change of key , which T. Adorno regarded as a “criticism” of through tonal gravity, which naturally led toatonality or pantonality [280] . Mahler's orchestra combines two trends that are equally characteristic of the beginning of the 20th century: the expansion of the orchestral composition, on the one hand, and the emergence of a chamber orchestra (in the detailing of texture, in the maximum identification of the possibilities of instruments associated with the search for increased expressiveness and colorfulness, often grotesque) - on the other. : in his scores the instruments of the orchestra are often interpreted in the spirit of an ensemble of soloists [279] . Elements of stereophony also appeared in Mahler's compositions , since in some cases his scores involve the simultaneous sounding of an orchestra on the stage and a group of instruments or a small orchestra behind the stage, or the placement of performers at different heights [279] . The path to recognition [ edit | edit code ]During his lifetime, the composer Mahler had only a relatively narrow circle of staunch adherents: at the beginning of the 20th century, his music was still too new. In the mid-1920s, she became a victim of anti-romantic, including " neoclassical " trends - for fans of new trends, Mahler's music was already "old-fashioned" [233] . After the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, first in the Reich itself , and then in all the territories it occupied and annexed, the performance of the works of the Jewish composer was prohibited [233] . Mahler was also unlucky in the postwar years: “It is precisely that quality,” wrote Theodor Adorno , “with which the universality of music was associated, transcendingmoment in it… that quality that pervades, for example, all of Mahler’s work down to the details of his expressive means — all this falls under suspicion as megalomania, as an inflated assessment of the subject of himself. That which does not renounce infinity seems to manifest the will to dominance characteristic of the paranoid …” [281] At the same time, Mahler was not a forgotten composer in any period: admirers-conductors - Bruno Walter , Otto Klemperer , Oskar Fried , Karl Schuricht and many others - constantly included his works in their concert programs, overcoming the resistance of concert organizations and conservative criticism; Willem Mengelberg in Amsterdam in 1920 even held a festival dedicated to his work [236] [233] . During World War II , expelled from Europe, Mahler's music found refuge in the United States., where many German and Austrian conductors emigrated; after the end of the war, together with the emigrants, she returned to Europe [233] . By the beginning of the 1950s, there were already a dozen and a half monographs devoted to the composer's work [282] ; many dozens of recordings of his compositions were counted: the conductors of the next generation have already joined the old admirers [283] . Finally, in 1955, the International Society of Gustav Mahler was created in Vienna to study and promote his work , and in the next few years a number of similar societies, national and regional, were formed [284] . The centenary of the birth of Mahler in 1960 was still rather modestly celebrated, however, researchers believe that it was this year that the turning point came: Theodor Adorno forced many to take a fresh look at the composer’s work when, rejecting the traditional definition of “late romanticism”, attributed it to the era of musical "modern" [285] , proved Mahler's closeness - despite external dissimilarity - to the so-called " New Music ", many representatives of which for decades considered him their opponent [233] [286] . In any case, just seven years later, one of the most zealous promoters of Mahler's work, Leonard Bernstein , could state with satisfaction: "His time has come"[287] [K 4] . Dmitri Shostakovich wrote in the late 1960s: "It is joyful to live in a time when the music of the great Gustav Mahler is gaining universal recognition" [290] . But in the 1970s, the composer's longtime admirers ceased to rejoice: Mahler's popularity surpassed all conceivable limits, his music filled concert halls, records poured in like a cornucopia - the quality of interpretations faded into the background; T-shirts with the words "I love Mahler" were sold like hot cakes in the United States [289] . Ballets [291] [292] were staged to his music ; in the wake of growing popularity, attempts were made to reconstruct the unfinished Tenth Symphony, which especially outraged the old malerologists [293] . Cinematography made its contribution to the popularization not so much of the composer’s creativity as of the personality of the composer — the films “Mahler” by Ken Russell [294] and “ Death in Venice ” by Luchino Visconti, imbued with his music and causing an ambiguous reaction among specialists . At one time , Thomas Mann wrote that the idea of ??his famous short story was greatly influenced by the death of Mahler: “... This man, burning with his own energy, made a strong impression on me. […] Later, these shocks were mixed with the impressions and ideas from which the short story was born, and I not only gave my hero who died an orgiastic death the name of a great musician, but also borrowed the mask of Mahler to describe his appearance "[295 ]. With Visconti, the writer Aschenbach became a composer, a character not intended by the author appeared, the musician Alfried, so that Aschenbach would have someone to talk to about music and beauty, and Mann's completely autobiographical short story turned into a film about Mahler [296 ] . Mahler's music has stood the test of popularity [K 5] ; but the reasons for the unexpected and in its own way unprecedented success of the composer have become the subject of special studies [289] . "Secret of success". Influence [ edit | edit code ]…What captivates in his music? First of all - deep humanity. Mahler understood the high ethical significance of music. He penetrated into the innermost recesses of human consciousness… […] Much can be said about Mahler, the great master of the orchestra, on whose scores many, many generations will learn. — Dmitri Shostakovich [297]

Research has found, first of all, an unusually wide spectrum of perception [298] . Once the famous Viennese critic Eduard Hanslik wrote about Wagner: "Whoever follows him will break his neck, and the public will look at this misfortune with indifference" [299] . The American critic Alex Ross believes (or believed in 2000) that exactly the same applies to Mahler, since his symphonies, like Wagner's operas, recognize only superlatives, and they, Hanslick wrote, are the end, not the beginning [ 167] . But just as operatic composers who admired Wagner did not follow their idol in his "superlatives", so no one followed Mahler so literally. To his earliest admirers, composersThe New Viennese School , it seemed that Mahler (together with Bruckner) had exhausted the genre of the "great" symphony, it was in their circle that the chamber symphony was born - and also under the influence of Mahler: the chamber symphony was born in the depths of his large-scale compositions, like expressionism [279] [279] [ 300] . Dmitri Shostakovich proved with all his creative work, as was proved after him, that Mahler exhausted only the romantic symphony, but his influence can extend far beyond the limits of romanticism [301] . Shostakovich's work, wrote Danuzer, continued the Mahlerian tradition "immediately and continuously"; Mahler's influence is most tangible in his grotesque, often sinister scherzos and in the "Malerian" Fourth Symphony [298] . But Shostakovich, like Arthur Honegger and Benjamin Britten , took over from his Austrian predecessor the dramatic symphonism of the great style; in his Thirteenth and Fourteenth symphonies (as well as in the works of a number of other composers) another innovation of Mahler found its continuation - "symphony in songs" [279] [298] . If during the composer's lifetime opponents and adherents argued about his music, then in recent decades the discussion, and no less sharp, has been unfolding among numerous friends [298] . For Hans Werner Henze , as for Shostakovich, Mahler was above all a realist; what he was most often attacked by contemporary critics for - "combining the incompatible", the constant neighborhood in his music of "high" and "low" - for Henze is nothing more than an honest reflection of the surrounding reality. The challenge that Mahler's "critical" and "self-critical" music posed to his contemporaries, according to Henze, "stems from her love of truth and the unwillingness to embellish conditioned by this love" [302] . The same idea was expressed differently by Leonard Bernstein: "Only after fifty, sixty, seventy years of world destruction ... can we finally listen to Mahler's music and understand that she predicted all this" [287] . Mahler has long been a friend of the avant-gardists , who believe that only "through the spirit of New Music" can one discover the true Mahler [303] . The volume of sound, the splitting of direct and indirect meanings through irony, the removal of taboos from banal everyday sound material, musical quotations and allusions - all these features of Mahler's style, Peter Ruzicka argued , found their true meaning precisely in New Music [304] . Gyorgy Ligeti called him his predecessor in the field of spatial composition [304] . Be that as it may, the surge of interest in Mahler paved the way for concert halls and avant-garde compositions [305]. For them, Mahler is a composer looking to the future; nostalgic postmodernists hear nostalgia in his compositions, both in his quotations [K 6] and in his stylizations to the music of the classical era in the Fourth, Fifth and Seventh Symphonies [273] [307] . "Mahler's romanticism," Adorno once wrote, "denies itself through disappointment, mourning, long remembrance" [308] . But if for Mahler the “golden age” is the times of Haydn, Mozart and the early Beethoven, then in the 70s of the XX century even the pre-modernist past seemed to be a “golden age” [307 ] .

In terms of universality, the ability to satisfy the most diverse needs and cater to almost opposite tastes, Mahler, according to G. Danuser, is second only to J. S. Bach , W. A. ??Mozart and L. van Beethoven [298] . The current "conservative" part of the listening audience has its own reasons to love Mahler. Already before the First World War , as T. Adorno noted, the public complained about the lack of melody among modern composers: “Mahler, who adhered to the traditional idea of ??melody more tenaciously than other composers, just because of this, made enemies for himself. He was reproached both for the banality of his inventions and for the violent nature of his long melodic curves…” [309] . After World War IIadherents of many musical currents diverged further and further on this issue with listeners who, for the most part, still preferred the “melodic” classics and romantics [310] , — Mahler’s music, L. Bernstein wrote, “in its prediction ... watered our world with rain beauty, which has not been equaled since then” [287] . |

Автор: Sonya Версія: 1 Мова: Англійська Переглядів: 0

|

Коротке посилання: https://www.sponsorschoose.org/a193

Коротке посилання на цю версію: https://www.sponsorschoose.org/n219

Автор - Sonya дата: 2023-05-31 07:58:22

Остання зміна - Sonya дата: 2023-06-03 16:38:13

|